“The Gonski” – A new Aussie Pizza (PISA)

Yes, a lame play on words, but still, the Gonski report – [Australian Government review of Funding for Schooling] could be considered a new “Aussie Pizza”. Lot’s of toppings, everyone has their own unique version, everyone would recognise one if they saw it, but no-one is sure that they can agree on what the “real” aussie pizza is. Of course, everyone will also fight over the last bit…

Ridentem dicere verum quid vetat.

Given the current difficulties of a minority federal government, compounded by the feckless machinations of a leadership dispute that does not deserve further focus, all within the context of current Australian policy seemingly polarised and bogged down in dogma, does not auger well for those hoping to see reform any-time soon. I imagine George Megalogenis would be suggesting that this is the perfect time and subject matter, for another Australian Moment..

Just to contextualise my comments..

Between 1980 and 2008, the richest 1% of Australians saw their share of total national income almost double, from 4.8% in 1980 to 8.8% in 2008 [OECD 2011] The richest 0.1% rose from 1% to 3%. At the same time, top marginal income tax rates declined markedly, dropping from 60% in 1981 to 45% in 2010. Nice work if you can get it..

We also know that during the last decade or so, enrolments in non-government schools have reached approximately 34% of total enrolments.

Higher than they have ever been.

We are also now witnessing a reform debate predicated on “choice” and maintenance of an apparent funding “right”. This leaves us with considerable dynamism in the policy space, dynamism, [in my view] without a broader focus or apparent purpose, other than some ill-defined notion of “choice” or reform of “poor teaching” or “under-performing” schools. I have no doubt there are both, but the causal relationships that much international policy appears to be based on, is perhaps, more suspect than we understand. The most current example of this challenge can be found here [Teacher Quality Widely Diffused, Ratings Indicate].

During such change in Australian education funding, enrollment patterns and the rise of comparative metrics to begin measuring the things we value [which I approve of i.e MySchool or OnTrack], two questions seem to continually present themselves in all this data and debate.

One. Is there a correlation [and/or a causal link] between the increase in non-government school enrollments and the subsequent drop in PISA scores?

Two. How can we concurrently debate policy priorities that focus on under-performing schools and teachers while simultaneously accepting the “high-performing” status of the Australian school system over such a long period of time? [Yes of course the regional/state differences are large, but you get my drift I hope….

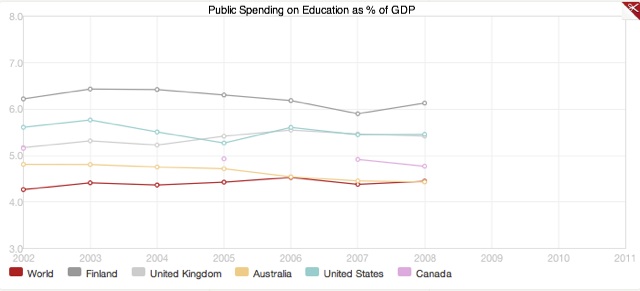

Australian spending on education as a percentage of GDP during [roughly] this same period, is now at or below a global average, with many major trading partners exceeding that spend, not all, I must say, with the results that we [still] experience. It would seem from a raw “productivity” point of view, we are still a very high achiever!

A challenge for our Federation!

My second graphic is a construct of the relative positioning of Australian student attainment on PISA tests since 2000.

In summary, we have been a consistently high performing country since PISA records began.

The results do indicate that there is both RELATIVE change and ABSOLUTE change in Australia’s results.

It suggests we are a bit weaker [over time] in Maths rather than Reading and Science. In science in fact, our absolute result [527] has not altered.

It also suggests that we are loosing ground in the comparative performance of our “top-end” students.[Not shown in this graph]

Note: Flash is required. My apologies to iPhone and iPad users.

In the past week, I was at a friend’s 50th Birthday party and I was speaking with another friend who is an experienced deputy-principal of a State Secondary College.The conversation inevitably turned [rather quickly in-fact] to the review that was about to be released [Gonksi]. He lamented..

I am so tired of the “let’s train teachers”, “let’s make teacher’s better” mantra, asserted my principal-friend.” What about the 60%+ non-school factors that effect student outcomes?”..

I have no doubt he was lamenting the apparent lack of trust in the profession as a whole. Something, I think, the profession itself should work on also, but that is for another time.

He had just experienced a particularly challenging week with parents and students, who, let’s just say, did not see the “point of education”. He has a point. It was also very pleasing to hear such focused knowledge about the national data from a school leader [while one would expect this, it is not evident from a general review of media coverage that school leadership is credited with such focus or knowledge]. He has been in the game 30+ years, has worked with enough teachers to know that there are some duds, but also knows the majority do a good job and some, if not many, do a great job.

If you think that is an “apologist” view [whatever that means in the current debate], i.e “most teachers” do a good job, I would direct you to the Australian mean scores for PISA Maths, Literacy and Science for the last twelve years [above] . It astounds me that we can contextualise a national debate on the grounds of “failing schools” and bad, lazy inept teachers, apparently the same bad, lazy inept teachers that have “produced” Australia’s results as one of the most consistently high-performing countries in the OECD since records began.

The scoreboard for international education “comparison”.. [yes I know that irks many..]

In 2000 - Australia was second in the world In 2003 - Australia was second in the world In 2006 - Australia was Sixth in the world In 2009 - Australia was top ten and...

all current [2009] results are [statistically] significantly above the OECD average.

The school, district and regional data my friend refers to suggests that within the socio-economic environment his school operates, they do a “reasonable” job of bridging the the forms of social and human capital students require to have better outcomes than previous generations. Of course, no-one I know in the profession wants to settle for “reasonable”.

My Principal friend is acutely aware, more so than most parents, media commentators or it appears, some policy makers, that the overwhelming focus of education policy debate in Australia for well over a decade has focused on the 32% variation in student achievement not explained by student social background. This is the bit that school systems think [and rightly so] that they can [should] “fix”. The problem becomes if that is all they do, or more importantly, if that becomes the sum of the total policy debate.

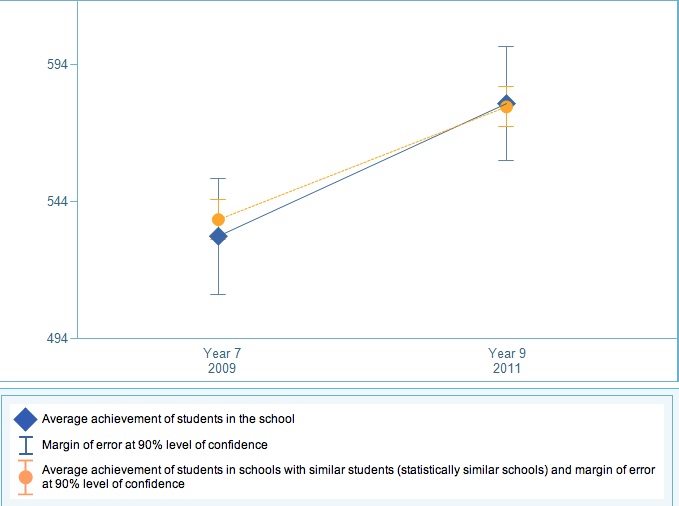

For the record, I could have taken any number of local school’s NAPLAN results and without specific selection, the data demonstrates that taking students who are well below the starting scores for the state average, these students GAIN substantially and at a rate that is consistent with the trends expected. It also shows that in fact, these schools do better in many cases than schools with similar students.

It serves many to have a narrower debate than I believe we need. The shift of student enrollments to non-government schools and the concentration of lower-performing students in many government schools is a challenge often simply ignored, it appears, by many policy makers.

This still leaves us with 40% of the variation between schools that relates to student social background and 28% of the variation that is explained by the social background of schools. Eric Hanushek, writing in 2008 about the concerns of the positioning of US students and the US Education system in the OECD results [way below Australia] referred to research that showed that the cognitive skills of a nation’s students have a large impact on its economic growth. He stated,

A more direct measure of a country’s human capital is the performance of students on tests in math and science, something that might be called the average level of “cognitive skills” among those entering a country’s work force.

In other words, what is learnt in school is the key to the link between educational attainment and a nation’s economic growth. Simply staying in school is not enough.

If you put the current impact and experiences of the Global financial crisis in the context of not only government fiscal and monetary responses [which politicians can rightly claim some credit for], the relative strength of a nations average level of “cognitive skills” might also suggest that Australia’s high-performing education system greatly assisted in ameliorating the impacts of such downturns because of the inherent depth and flexibility of skills within our workforce, provided of course, by the education system…

Of course, when it comes to the issues of achievement and equity within the Australian school system, “reasonable” is not enough, but perhaps within current resourcing structures and public confidence, it is all we can honestly expect without further reform, because as we are witnessing, the status-quo only sees our position fall against those that are “improving”.

The danger from a policy perspective is that we are fixing things that are not broken…

Certainly the social and economic challenges many of our partners in the OECD are facing should be a stark reminder of what disengagement and disenfranchisement looks like.

There is no doubt that our State and Federal policy positions appear somewhat “panicked” with “crises” and “challenges”.

The broad take-away messages from the most recent PISA results suggest that:

Mean mathematics performance remained unchanged, on average, across the 28 OECD countries with comparable results in the PISA 2003 and 2009 surveys. However, it improved in six of these countries and in two partner countries. Mexico and Brazil showed the largest improvements over the period: 33 and 30 score points, respectively, or around half a proficiency level. Mathematics performance declined in nine OECD countries over the same period. In the rest of the 39 countries that have comparable results in both assessments, there was no significant change.

Germany’s mean performance in mathematics improved from OECD average levels in 2003 to above-average levels in 2009.

In eight of the nine countries where mathematics performance declined, students had scored above the OECD average in 2003. Despite a drop of 12 score points, the Netherlands remains among the highest- scoring countries in the PISA mathematics survey.

In Australia, Belgium, Denmark and Iceland, mean scores also remained above the OECD average in 2009.

Of note, Australia “only” dropped 10 points in this time. Yes, Netherlands score is higher, but it should be noted is also DROPPING faster than Australia.

Tell me again what the issues REALLY are in Australia?

It still surprises me that we cannot have this level of debate without it being seen as a “class war” or something that is going to rip rights away from “hard working families” that have a “right to choose”. Of course they do. The challenge should be explaining to the populace what is in the best long-run interests of the country, particularly when we have such access to wealth and infrastructure, compared to the vast majority of our trading partners. Our competitive advantage is apparently vast, yet our political will and leadership seems to be satisfied with the odd “tax-break” or “surplus setting”.

Judith Sloan, writing recently in The Australian about the GONSKI review, put it as succinctly and un-emotionally as any with as razor-sharp a mind as hers can. Simply,

It would be fairer and cheaper for some rich schools to lose funds…and for those schools with very high SES scores – that is, with very high-income-earning parents – federal government funding should be phased out altogether.

The Gonski report has a student-centred resourcing standard at its core. As Jack Keating writing in the Australian pointed out:

Paul Keating did warn against getting between a state premier and a bucket of money, but the attitude of the states, and also the non-government schools, is that the money should just be left on the stump.

I have certainly seen evidence at a local level across a number of geographic regions in Victoria, the very real collaboration and co-operation that can occur between government and non-government schools to effect change in the best interests of all schools in a region. There are myriad examples of work within the Local Learning and Employment Network “LLEN” initiative in Victoria that pre-supposes a level of good-will and willingness to work on behalf of all students within a region. This co-operation often extends to significant capital and recurrent funding collaboration across all school sectors. This is certainly a governance and local over-sight model that would have much to offer when it comes to the practical implementation needs of Gonski and a national/cross sectoral approach to funding.

Certainly, there are leaders within each sector that would work to ensure the net benefit of students in “their” region, as opposed to “just” their school.

The Tail ? The question of equity.

We are not [thankfully] a homogenous society, our public institutions [schools, hospitals, courts] will reflect and mirror the very strength of our diversity, yet the lag in operation of such institutions also means that by the time we have identified a societal/socio-cultural shift or change [i.e long-term youth unemployment or divorce rates or rural disadvantage, even climate change], we often have considerable lag [if at all] in a policy response, let alone a subsequent “on the ground” operational response. This all assumes of course, that we even recognise and accept the data when we see it….

Never have we needed real-time reporting, randomised policy trials [PDF] and a combined federal-state approach to such challenges.

I fear we are increasingly working within the policy paradigm of “what’s in it for me” and playing to the less noble elements of the voters psyche.

Most certainly our ability as a nation to share and commit to altruistic policy positions, (i.e I will pay a little more tax so waiting times drop in hospitals) seems to have evaporated. Perhaps, if one is being pessimistic, this also includes our apparent lack of interest in the correlation of a young person’s post-code to their educational and socio-economic outcomes.

Of course this is not a one-size fits all argument, but our apparent lack of ability to address nuance in the needs of geographically and socially diverse groups within Australian society, particularly when it comes to education, is confounding.

Having parents that lived through the depression and world wars, I know the “builder generation” are turning in their graves…

In other words, things take time and with a level of polarised public debate that is not led by evidence nor, it appears, a genuine bi-partisan will, little forward movement occurs and in fact, ground is lost.

If ever we needed genuine leadership in this field, it is now.

This is the first time in our history that we have access to such long-run data sets for the sector of the economy that I have heard a Minister of the Crown refer to as, the notorious “education black-hole”.

The next three months will determine if the new “Aussie Pizza” the “Gonski” will be lovingly baked, topped with all the best fillings and delivered warm and on time to those that have ordered it, or perhaps, will simply go cold in the back seat of some policy van without a driver…??

Yes, I think I have pushed that analogy far enough…